Citroën has never been a company that believed it should simply go along to get along. It has always proudly done things differently, in its own unique and very Gallic way and this has led to some of the 20th century’s greatest automobiles; cars which still inspire desire and fascination to this day such as the Traction Avant, the 2CV, the DS and of course the SM. Citroën as a company has often paid the price for flying its own flag but continues to persevere to this day making quirky and thoughtful cars for the masses. It’s for these reasons that Peter Mullin, one of the world’s foremost collectors of French cars, has brought together the largest Citroën exhibit in US history at the Mullin Automotive Museum in California to celebrate “Citroen: The Man, The Marque, The Mystique.”

Birth of an Industrialist

Citroën was founded by André Citroën as a manufacturer of double helical gears for industry. Citroën didn’t invent this gear pattern but rather purchased the patent from a Polish carpenter after experiencing firsthand their relative lack of noise and much-improved efficiency over conventional helical gear designs. His company continued to manufacture gear sets until the outbreak of World War 1 when Mr. Citroën was called up as a reserve captain. During his time at the front, Citroën noticed that the French were woefully undersupplied, particularly when it came to artillery munitions. Believing that he could solve this problem by modernizing production, he secured government funding to build a factory in the suburbs of Paris on the banks of the Seine.

With the end of the first world war in 1918, Citroën soon found himself without a buyer for his wares and decided to bet his future on the success of the automobile, though this was far from a new industry to him. He had spent nearly six years with the Mors firm before the outbreak of World War 1. Again, using what he’d learned from Mors and from Ford, André Citroën dove headlong into the world of automotive manufacture with the Type A, Europe’s very first mass-produced automobile. The Type A was powered by a 1.3 liter water-cooled four-cylinder engine producing a respectable 18 horsepower. Nearly 25,000 Type A’s left the factory on the Seine, a far cry from the millions of Ford Model T’s built by Ford only a few years later, but impressive nonetheless.

The replacement for the Type A was the B2 which added a slightly more powerful engine, a marginally higher top speed, and more elegant body designs. The B2 was the start of the long-lived B-series of cars which continued all the way through the all-steel construction B12 and B14. The B12 also had the distinction of being the first Citroën with four-wheel drum brakes. Previous models were only equipped with brakes on the rear axle. Citroën’s next technological tour de force took all of the innovations pioneered on the earlier cars and for the most part, kicked them to the curb in favor of building something truly new. Enter the Traction Avant.

First Big Hit

The Traction Avant can arguably be called André Citroën’s crowning achievement. More than almost any vehicle, the Traction Avant was the first mass-market application for a number of incredible technologies, many of which stay with us to this day. Traction Avant is, of course, French for Front Drive. While the Traction may not have been the first car sold to the public with front wheel drive, it was certainly the most widely sold and affordable. The car also utilized a unique unitized body construction, eschewing the heavy frame of previous models. These two traits allowed the Traction Avant to ride lower than many of its competitors and gave its designer, Flaminio Bertone a blank canvas from which to design. Many of the other technological advances such as four-wheel independent suspension (a torsion bar design licensed from Ferdinand Porsche) came at the request of Citroën’s young chief engineer, André Lefèbvre, himself a former aircraft designer who had worked with the famous Avions Voisin.

Despite all of the praise heaped lovingly upon it by the automotive press and the public at the time of its debut, the Traction Avant was the victim of circumstance. The incredibly short design time and the razing and rebuilding of the Citroën factory along with the worldwide implications of the global financial crisis meant that despite selling nearly 760,000 units, the car spelled the end of André Citroën’s leadership of the company he founded. The French government stepped in and negotiated with Citroën’s chief creditor, Michelin Tire, to take over the company and mandated that André Citroën step down as president. After his time as chief ended, he rather quickly succumbed to cancer and died in 1935 at the age of 57.

The Highpoint: The Mid-Century era

After the death of Mr. Citroën, with the company under new management, Citroën’s fortunes began to improve. The Traction Avant, with a new and more powerful engine began to sell in greater numbers. The vice-president of the company, Pierre Boulanger, had an idea for a new vehicle that would be an antithesis of the Traction Avant. This vehicle, specifically designed to motorize the rural farmers of France, many of whom still relied upon horse and cart, would be as cheap and functional as was humanly possible to design and was called initially Toute Petite Voiture or “Very Small Car.” The design brief for the car which would come to be known as the 2CV, was simple if a bit odd. The car must be economical to purchase and to own, it must be able to carry a load of potatoes to market, it must be easy to manufacture and most famously it was expected to carry a basket of eggs across a plowed field without breaking any of them.

The production version of the TPV wouldn’t debut to the public until 1948 at the Paris Salon. The international press response was dubious, but the French people adored the car and thousands of orders were taken. The backlog of orders for the 2CV stretched to more than six years. The production vehicle would be powered by a small, simple air-cooled horizontally opposed engine which was cheaper and easier to start in the cold than the prototype’s water-cooled design. The vehicle would front wheel drive and be geared such that it could be driven at then-current road speeds despite having low power. The suspension, another four-wheel independent set up, featured two unique spring boxes mounted near the rocker panels in the center of the car which allowed for incredibly soft spring rates and very long suspension travel making for a comfortable, if floaty, ride. To keep the cost of materials down, the body was made of cheap and somewhat thin metal steel, corrugated to add strength. The 2CV remained in production until 1990.

The car for which Citroën is arguably best known was debuted to the public in 1955. To soften the blow somewhat for what was sure to be Citroën’s most outlandish and unique car yet, they began to offer the aging Traction Avant with a hydro-pneumatic rear suspension in 1953. They also began to offer it for the first time in a color other than black. When the DS made its splash at the Paris Motor Show, the world had never seen anything like it. At a time when American cars were huge, ponderous and chrome laden, the DS was lithe and sleek. It looked so much like a space ship that a specially prepared body was displayed as a rocket, ready to launch. The motoring public was so taken with the DS that Citroën received 750 orders within 45 minutes of its unveiling. By the end of the show they would go on to receive many thousands more.

The party trick of the DS - apart from its incredibly elegant body designed by Flaminio Bertone - was its revolutionary hydro-pneumatic four-wheel independent suspension. This system not only controlled the spring and shock absorption function of the car, it also allowed ride height to be adjusted from inside the vehicle as well as three-wheeled operation and incredibly simple tire changes. This system was also tied into the brakes which tossed away the tried and true brake pedal for a mushroom-shaped button on the floor of the car. Furthermore, the system was tied to both the power steering, controlled by a unique single-spoked steering wheel, and the semi-automatic transmission. The elegant body was more than just a pretty face for the car, with its incredibly low-drag shape, even the modest 1.9-liter engine derived from the Traction Avant was able to propel the car to a top speed of 85 miles per hour. When the DS21 made its debut several years later, that rose to 105 miles per hour.

The great success of the DS was not merely in its triumph of technology, but in how quickly and wholeheartedly the French people adopted this strange and beautiful device into their everyday lives. The DS was the car for anyone, even the French presidents rode in them, most famously Charles De Gaulle who was able to narrowly avoid assassination by the group known as the Black Hand thanks to the DS’ ability to remain stable even with two tires shot out. The car, which has been out of production since 1975 remains near and dear to the hearts of all French people and is a beloved sight around the world. With the success of the DS, Citroën felt it appropriate to offer a lower-cost version known as the ID. This car kept the DS’ famous suspension but opted for more conventional brakes, steering and transmission to bring the cost of the car down. These cars proved incredibly successful in long distance, endurance-based rallies.

The proud Citroën tradition of taking risks didn’t die with Mr. Citroën, and this was evidenced in the decision to purchase struggling Italian automaker Maserati in 1968. Maserati had a reputation for building beautiful and fast, if somewhat temperamental sports and grand touring cars and Citroën hoped that through its merger, it could make use of some of Maserati’s engine building expertise while also trickling some of the Citroën quality up to the Italian brand. The result was one of the world’s greatest and most misunderstood cars, the Citroën SM.

The SM bore many similarities to its predecessor, the DS in that it shared the earlier car’s hydro-pneumatic suspension, steering, and brakes. Where it differed significantly was in its intended purpose and its means of motivation. Gone was the reliable old four-cylinder engine from the DS, and in its place was a specially designed Maserati V6 engine, first with carburetors and later electronic fuel injection. This engine was designed on a severely truncated timetable and as such had more than its fair share of teething troubles. The engine was essentially mounted backwards in the car to accommodate the front wheel drive design so beloved by Citroën.This engine was good enough to give the SM a top speed in excess of 140 miles per hour, making it the world’s fastest production car at the time.

The braking system on the SM was particularly lauded by critics with the SM achieving the shortest stopping distance of any car ever tested by Popular Science up to that point. The SM, rather than being conceived as a sports car, was built to be a grand tourer and thanks to Citroën’s exceptionally comfortable seats, a massive fuel tank and untold levels of comfort being derived from the suspension, owners were finding themselves able to cruise for long distances at 120+ miles per hour in relative safety and security. The SM’s crowning achievement was its being named Motor Trend’s 1972 Car of the Year, something which proved to be a rather controversial choice.

Together at The Mullin

“After learning about Citroen the man, the company and the machines that he created I became somewhat obsessed, doing research and gathering vehicles from across the globe for several years,” said museum founder, Peter Mullin. “The result is “Citroen: The Man, The Marque, The Mystique,” – what we believe is the first exhibit dedicated completely to Citroen in the United States.”

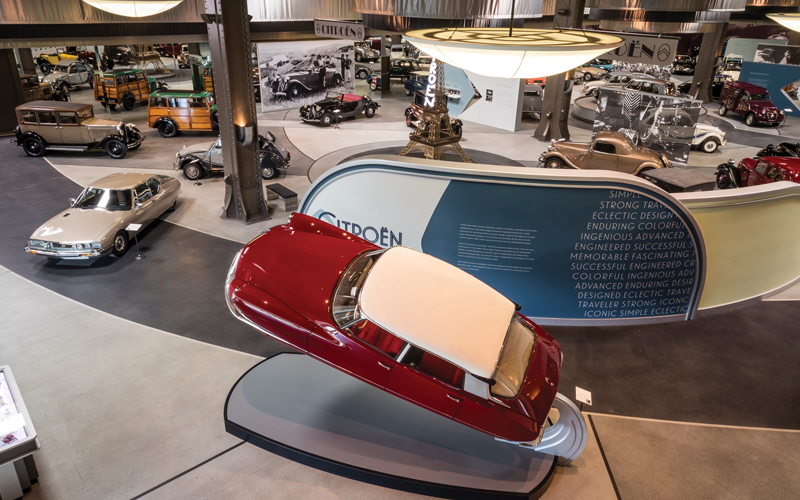

The Mullin’s exhibition brings together history’s most significant Citroën models. In fact, 46 of the world’s most historic and unique Citroëns fill the museum floor. The collection includes a number of vehicles bodied by French coachbuilder Chapron, a rare twin-engined 2CV Sahara, a Traction Avant Cabriolet and an iconic HY Van. Visitors will also get to see modern Citroëns such as the 2007 C6 and the 2009 C3 Pluriel as well as several late production model 2CVs dating from the 1980s and early 1990s, none of which were ever sold in the U.S.

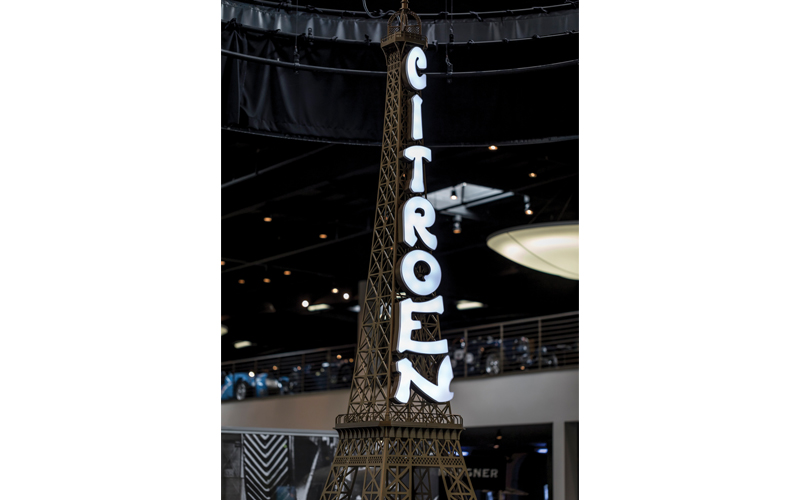

A 1967 Citroen ID19 ‘Rocket’ greets visitors as they enter the exhibit. The display is a tribute to a Citroen’s car sculpture unveiled at Turin in 1957 and as some visitors point out, the display looks like it was pulled from The Jetsons. Also on display is a small-scale Eiffel Tower, which is a true testament to Andre Citroens “marketing genius.” In 1925, Citroen convinced the Paris city fathers to light up the Eiffel Tower at night in a glorious light show. That was not an easy prospect, particularly then, and Citroen offered to pay for it, with a catch – the Tower was lit with the letters C I T R O E N from top to bottom. It was, and remains today, in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s largest advertising sign.

To appreciate Citroën as a brand means you must relax your preconceptions of what a car can be. “Throughout history, some of the best ideas and most brilliant leaps forward have been met, initially, with derision and confusion,” said Mullin. “I believe the willingness to suspend judgment long enough to learn what these amazing little cars can do drives the mystique of Citroen.” André Citroën took his own ideas of what a car could be and sent them out into the world where they arguably improved automobiles as a whole. He was many things, as his cars are many things, but boring and unassuming was never one of them. The Mullin’s exhibition represents the largest and best assemblage of Citroëns ever in the US and for those passionate about the brand, a trip to see “Citroen: The Man, The Marque, The Mystique,” should be considered mandatory.